Dashboards have become the default symbol of modern client advisory services. When firms want to signal sophistication, they show visuals: real-time KPIs, clean charts, and automated reports. Clients see movement. They see color. They see activity.

But seeing activity is not the same as gaining direction.

Many CAS leaders privately recognize a tension: dashboards are improving, yet advisory conversations aren’t necessarily getting sharper. Meetings still revolve around reviewing numbers instead of using numbers to steer decisions. The dashboard exists. The direction doesn’t always follow.

The issue is not that dashboards are failing. It’s that dashboards are descriptive tools being asked to perform an interpretive role. And interpretation doesn’t come from visualization; it comes from how data is structured, analyzed, and translated into business logic.

The missing piece is not more reporting sophistication. It’s analytical intent built into the data itself.

The data problem hiding inside a dashboard problem

Most CAS dashboards sit on accounting data designed for compliance and recordkeeping, not for decision intelligence. General ledgers capture transactions faithfully, but they don’t automatically organize information in ways that answer business questions.

A dashboard built on unmodeled accounting data will always lean toward hindsight:

- What happened last month

- What changed from the budget?

- Which account moved

Those are valid observations, but they stop short of operational meaning. Business leaders don’t run companies at the account level. They run them through drivers: pricing, capacity, utilization, customer mix, cost structure, and working capital cycles.

When dashboards don’t reflect those drivers, they force advisors to interpret manually every month. The insight exists, but it’s reconstructed from scratch each time. That makes advisory inconsistent and dependent on individual talent rather than repeatable design.

Direction emerges when the data model mirrors how a business actually operates.

Instead of asking:

“What did expenses do?”

The model should make it easy to ask:

“What operational lever pushed expenses?”

That shift requires moving beyond account-based reporting into driver-based structuring.

Please find below a previously published blog authored by Dipak Singh: Why Visibility Alone Doesn’t Create Advisory Value

Why visibility doesn’t automatically produce insight

A common assumption in CAS is that if clients see more data, they’ll naturally make better decisions. In practice, the opposite often happens. Increased visibility without context amplifies noise.

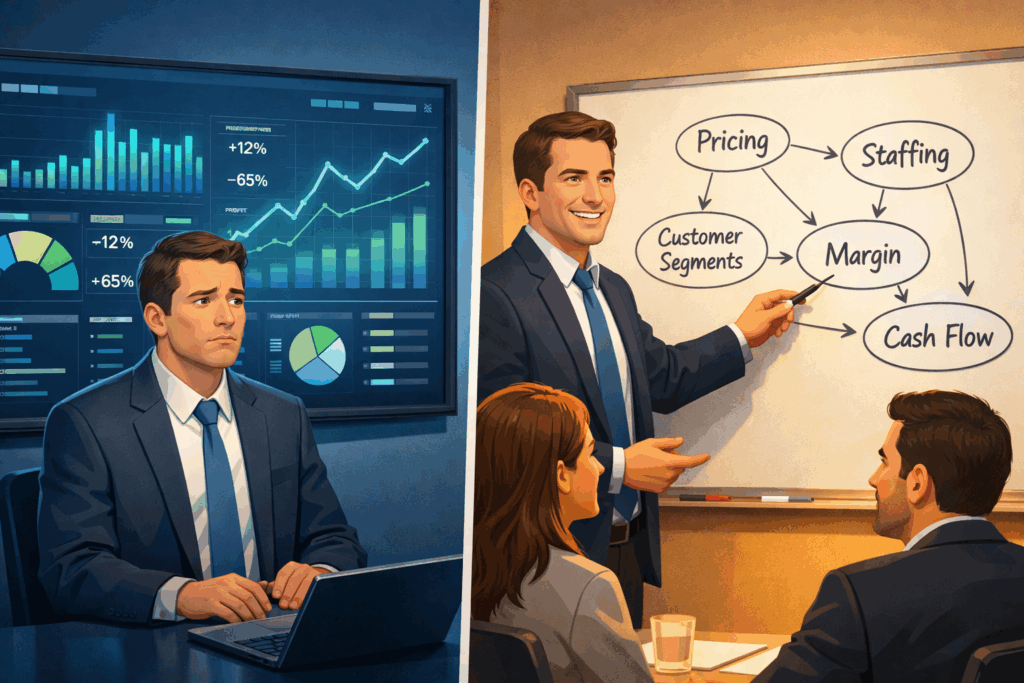

A dashboard might show:

- Revenue growth

- Margin pressure

- Rising payroll

- Strong cash balance

Individually, each metric looks healthy or explainable. Together, they may signal an unsustainable growth pattern. But dashboards rarely assemble relationships between metrics. They present snapshots, not systems.

Insight comes from linking measures:

- Growth relative to staffing

- Margin relative to pricing strategy

- Cash relative to burn rate

- Customer acquisition relative to retention

When relationships are embedded into analysis, the dashboard stops being a gallery of charts and starts functioning like a diagnostic instrument.

This is where data engineering meets advisory. The role of CAS is not just to present figures; it is to design analytical relationships that surface tension, risk, and opportunity automatically.

Direction is the byproduct of structured comparison.

The difference between reporting data and modeling data

Most CAS environments are optimized for reporting pipelines: clean inputs, standardized outputs, and reliable refresh cycles. That’s necessary infrastructure. But modeling requires a different layer of thinking.

Reporting answers:

“What is the number?”

Modeling asks:

“What drives the number?”

That distinction changes how data is stored and categorized. Instead of organizing purely by chart of accounts, mature advisory datasets introduce operational dimensions:

- Customer segments

- Product or service lines

- Capacity units

- Labor categories

- Acquisition channels

- Lifecycle stages

Once data is tagged along these dimensions, patterns become visible without heroic effort. Advisors don’t have to invent insight during meetings. The structure of the dataset guides the conversation.

For example, margin compression stops being a vague observation and becomes traceable:

- Is it concentrated in a customer segment?

- Is it tied to discounting?

- Is it labor intensity?

- Is it vendor dependency?

Direction is not a clever comment. It’s the natural conclusion of a well-structured dataset.

Where effective CAS actually uses data differently

High-performing advisory teams treat financial data less like a report archive and more like an operating model. Their dashboards are not endpoints; they are interfaces into a deeper analytical system.

What distinguishes them is not visual polish. It’s how questions are anticipated in the data design:

- Can we isolate growth quality, not just growth rate?

- Can we see profitability by decision unit, not just by account?

- Can we detect stress before it shows up in cash?

- Can we separate structural shifts from seasonal noise?

When the data answers these questions reliably, advisory becomes calmer and more confident. Conversations shift from explaining fluctuations to discussing strategy.

Clients experience a subtle but powerful change: numbers stop being historical artifacts and start behaving like decision signals.

That is the moment dashboards become directional tools.

What CAS leaders should internalize

The evolution from dashboards to direction is not about layering more analytics on top of existing reports. It’s about redesigning how financial data is organized so insight becomes inevitable rather than accidental.

Three principles anchor that shift:

First, data should mirror how the business runs, not how accounting records it. Advisory strength comes from operational alignment, not chart-of-account elegance.

Second, relationships matter more than isolated metrics. Direction lives in comparisons, ratios, and patterns, not single numbers.

Third, insight should be engineered upstream. If advisors must reinterpret raw data every month, the system is under-designed. The goal is repeatable intelligence, not heroic analysis.

When CAS practices internalize these principles, dashboards stop being static displays. They become active instruments that guide conversations, highlight pressure points, and frame decisions before clients even ask the question.

That is how data earns its advisory role.

The Core Takeaway

Dashboards are not the end state of data maturity. They are the interface. Direction comes from how the data underneath is modeled, connected, and interpreted. CAS firms that invest in analytical structure, not just visual reporting, turn financial information into a strategic asset clients can actually steer with.

And once clients start steering with your data, the nature of the relationship changes.

Reporting becomes background. Direction becomes the product.

Get in touch with Dipak Singh

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What’s the difference between a dashboard and a directional data system?

A dashboard visualizes metrics. A directional data system structures and connects metrics around operational drivers so insights surface naturally. The dashboard is the interface; the model underneath determines whether it produces clarity or noise.

2. Why don’t traditional accounting systems support strategic advisory well?

Accounting systems are optimized for compliance and transaction accuracy. They record what happened but don’t inherently organize information around operational drivers like pricing, capacity, or customer behavior. Advisory requires that additional modeling layer.

3. How can CAS firms begin shifting toward driver-based modeling?

Start by identifying the key operational levers in a client’s business, revenue drivers, cost drivers, and working capital cycles. Then restructure financial data to align with those levers, adding dimensions such as customer segments, service lines, or capacity units.

4. Does this require new software?

Not necessarily. Many firms already have capable tools. The limitation is often structural design, not technology. Before replacing platforms, evaluate whether the underlying data model supports driver-based analysis.

5. What changes when data becomes directional?

Advisory conversations shift from explaining variances to discussing decisions. Insights become repeatable, meetings become more strategic, and clients begin using financial data proactively rather than reactively.